“Abbiamo un obiettivo ambizioso: investire nella conoscenza, nutrimento per l’anima, necessaria per un essere umano alla stessa stregua del cibo"

Fondazione Mirella Vitale ETS

Fondazione Mirella Vitale ETS

Sede legale: Via Generale Di Maria, 43

90141 Palermo

C.F.: 97376260820

Contatti

E-mail:

fondazionemirellavitale@gmail.com

Front: Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology

ORIGINAL RESEARCH Article published 20/11/2025

Adapting to Mediterranean island environments: prehistoric human interaction with plants and animals at Piano dei Cardoni (Ustica) and Mursia (Pantelleria)

Claudia Speciale1,2* Marialetizia Carra3 Fabio Fiori3 Vito Giuseppe Prillo4 Ethel Allué1,2 Maurizio Cattani5

- 1 IPHES-CERCA, Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution, Tarragona, Spain

- 2 Department of History and History of Art, Rovira i Virgili University (URV), Tarragona, Spain

- 3 ArcheoLaBio, Bioarchaeological Research Center, Department of History and Cultures of Civilizations, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

- 4 Department of Cultural Heritage, University of Padua, Padua, Italy

- 5 Department of History and Cultures, University of Bologna, Bologna, Italy

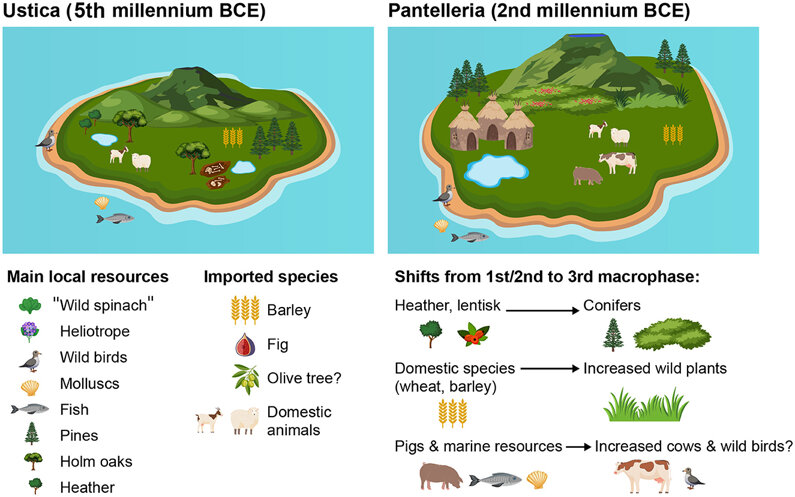

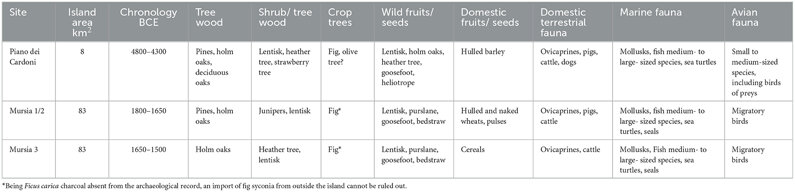

This study investigates prehistoric human adaptation to small Mediterranean island environments through the archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological analysis of two key sites: Piano dei Cardoni (Ustica, Neolithic) and Mursia (Pantelleria, Bronze Age). Both volcanic islands, diverse in size, landscape characteristics, and occupation chronology, offer an ideal framework for exploring how early human communities managed limited island resources, overcame ecological constraints, and established sustainable subsistence systems.

On Ustica, permanent settlement during the Middle Neolithic (c. 4800–4300 BC) is reflected in a diverse exploitation of local vegetation and wildlife resources. Archaeobotanical evidence suggests the co-occurrence of plant species associated with natural and anthropogenic habitats, including barley, fig, olive, and mastic, which may indicate the deliberate introduction of tree crops for long-term occupation. Shrub and woodland species were used without evident overexploitation, and faunal remains demonstrate a subsistence economy based on sheep and goats, supplemented by wild birds and marine resources. The absence of large mammals and the small size of domestic animals highlight adaptive strategies in a context of limited resources.

In contrast, Pantelleria in the Bronze Age (c. 1800–1500 BC) exhibits a more structured subsistence model within a larger and ecologically complex island. The Mursia settlement reveals a shift in plant use during its occupational phases, from agriculture based on cereals and legumes to a greater exploitation of wild plants such as purslane and cash-crop trees such as figs. Charcoal likely indicates a technological selection of plant species, with a predominance of pine, juniper, and heather. Zooarchaeological data reveal a dominant use of sheep and goats, marine fish, and mollusks, with a possible reorganization of farming strategies over time.

The comparative analysis reveals both continuity and divergence in island adaptation. Although both sites demonstrate human resilience through mixed subsistence strategies combining agriculture, food gathering, and marine exploitation, local environmental and cultural factors determined distinct responses. The findings highlight the importance of interdisciplinary approaches in understanding human-environment interactions and the role of islands as dynamic laboratories of ecological and cultural experimentation during prehistory.

Graphic Abstract

Graphic Abstract

1. Introduction

The historical heterogeneity of the Mediterranean region's landscape exemplifies how humans can, through short-term decisions, "create productive ecosystems in otherwise marginal environments" (Braje et al., 2017). The negative effects of human impact have led to the creation of thriving artificial ecosystems, generally endowed with the resilience to withstand fluctuations. The creation of complex ecosystem interactions was paradoxically triggered by the advent of humans, as demonstrated by an initial increase in species richness (Lomolino and Van der Geer, 2023). This process ultimately gave rise to a landscape less rich in biodiversity, while maintaining for the most part the same structure as in subsequent prehistory.

In addition to the general trend of biodiversity loss, resources on small islands (<100 km2), regardless of geomorphology, altitude, or other geographic features, are inherently limited (Keegan et al., 2008). This limitation arises from the islands' intrinsic trophic constraints, which depend on their area (Brose et al., 2004). However, the concept of "adaptability" in human colonization is shaped not only by natural factors, but rather by the choices humans make and how they respond to the challenges of the new island environment (Giovas, 2016).

Resource management, particularly subsistence resources, is therefore critical to achieving successful long-term colonization and settlement by newcomers, especially if they are at the top of the food chain like humans (Newsom and Wing, 2004) and are significantly exposed to stochastic perturbations (Cherry and Leppard, 2018). Colonization by hunter-gatherer-fishermen groups has generally involved less drastic environmental changes than those of agricultural societies, which often introduced a wider range of external plant and animal species (both cultivated and wild), whether intentionally or not (Hofman and Rick, 2018; Plekhov et al., 2021).

Unless there are natural sedimentary sequences to compare with—and this is especially true on larger islands—the effects of human arrival on islands are visible almost exclusively through archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological datasets (Pasta et al., 2022), so a reconstruction of the pre-human environment is not always easy to conceive. In these cases, archaeological data represent the almost unique paleoenvironmental and paleovegetation indicators available to researchers (Pasta and Speciale, 2021).

Among others, the introduction of sheep and goats is a key factor in the transformation of pre-human vegetation on small islands, particularly due to the natural absence of large wild herbivores. The high tolerance of goats to a wide range of climatic conditions allows introduced populations to grow rapidly if not controlled (Leppard and Pilaar Birch, 2019). This dynamic has recently attracted attention on the island of Alicudi (Aeolian Archipelago, Messina, Sicily), where feral goats have thrived in the context of widespread landscape abandonment (Figure 1). Their presence could rapidly lead to overgrazing, especially on a 5 km2 island. Furthermore, the introduction of other species that may affect the local vegetation such as rodents and lagomorphs or small carnivores could be induced directly or indirectly by humans (Masseti, 2003), sometimes as early as the Early Neolithic (Trantalidou, 2008).

Figure 1. One of the feral goats on the top of Alicudi island (September 2023).

Figure 1

The reliance of agricultural communities on a wide and diverse range of plant and animal species has helped overcome the intrinsic trophic limitations of Mediterranean islands, making even very small and marginal island environments suitable for human settlement (e.g., McLaughlin et al., 2018; Scerri et al., 2025). The prevalence of more drought-tolerant sheep and goats compared to cattle and pigs at sites on smaller, ecologically marginal islands provides supporting evidence (Ramis, 2014). The same is true for crops, with significant reliance mainly on hulled barley (Speciale, 2021; Speciale et al., 2023 , 2024a).

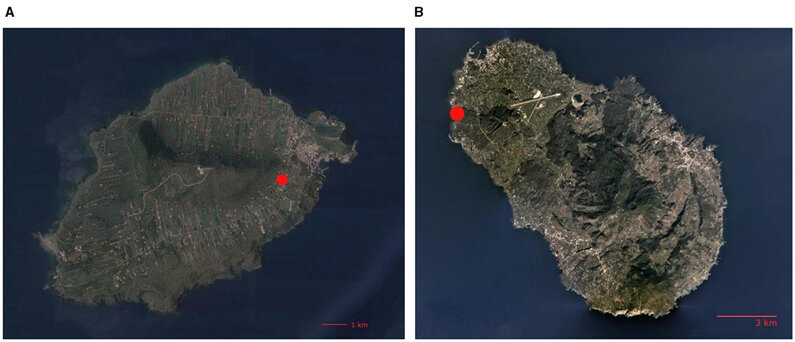

This study addresses the following research questions in the two case studies, Ustica and Pantelleria (Figure 2):

- How did prehistoric human communities adapt their subsistence and settlement strategies to the ecological constraints of small volcanic islands in the central Mediterranean?

- Which archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological indicators can be interpreted as signs of human adaptation?

- Do these indicators vary over time, particularly between the Middle Neolithic (mid-5th millennium BC) and the Middle Bronze Age (1800-1500 BC)?

Figure 2. Geographical location of the two case studies: Ustica and Pantelleria.

Figure 2

2. Geographic framework

Ustica Island is an extinct volcano located 60 km off the northwestern coast of Sicily, west of the Aeolian Islands. The emerged part of Ustica covers an area of less than 9 km2 and reaches an altitude of 248 m above sea level, at Mount Guardia dei Turchi (Figure 3A). Ustica is composed of volcanic rock and, to a lesser extent, marine and continental sedimentary deposits (de Vita and Foresta Martin, 2017). The island is rather suitable for human settlement, compared to other volcanic islands, thanks to the presence of two extensive former marine abrasion platforms on both the northern and southern sides, which offer ideal conditions for habitation and cultivation. Furthermore, the almost total absence of slopes and the geochemical nature of the soils allow the creation of small seasonal ponds (gorghi in the local dialect) for the natural collection of rainwater (Speciale et al., 2023). Piano dei Cardoni, a Neolithic site, is located in the southeastern part of the island, not far from the natural harbor of Cala Santa Maria, well-lit and protected from strong mistral winds.

Figure 3. ( A) Ustica and the location of the Piano dei Cardoni site; (B) Pantelleria and the location of the Mursia site.

Figure 3

The modern vegetation of Ustica is strongly influenced by its volcanic origin and the Mediterranean climate. According to the most recent census (2009), the island still hosts around 400 taxa of vascular plants (Speciale et al., 2023). The coast is home to halophilous plants such as Crithmum maritimum and species of Limonium. Inland, Mediterranean scrub dominates, with dense forests of Pistacia lentiscus, Phillyrea latifolia, and wild olive (Olea europaea var. sylvestris). On the rocky slopes, garrigue vegetation appears, composed of low shrubs such as Cistus and Euphorbia dendroides. Aromatic herbs, including thyme (Thymus capitatus) and rosemary (Salvia rosmarinus), are widespread. The prickly pear (Opuntia ficus-indica) has become naturalized, although it was introduced, and the caper (Capparis spinosa) grows spontaneously between walls and cliffs. In the higher and more sheltered areas there are clumps of Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis).

The island's fauna is modest on land, with reptiles such as the Italian wall lizard (Podarcis sicula) and a few small mammals, but its coastal and marine environments are particularly rich. Along the coast, rocky habitats are home to numerous invertebrates such as crabs, mollusks, and echinoderms adapted to tidal conditions. The cliffs provide nesting sites for seabirds including herring gulls (Larus michahellis), shearwaters (Calonectris diomedea), and European shags (Phalacrocorax aristotelis). The island is also located on a migratory route, attracting birds of prey and passerines that stop along the coastal areas. Groupers, barracudas, and pelagic species are commonly found in the surrounding waters, while sea turtles and dolphins are occasionally observed.

The island of Pantelleria, also of volcanic origin, is located in the center of the Mediterranean Sea, between Sicily and Tunisia; it is quite close to the African coast, located about 70 km away (Cape Mustafà near Kelibia, Tunisia), and a little further from the Sicilian coast (about 100 km); the highest peak, Montagna Grande, reaches an altitude of 836 m above sea level. Due to the high permeability of the soil and the local microclimatic conditions, the island has numerous but limited water sources, called buvire in the island dialect and easily accessible for exploitation. The surface of the island (83 km2), especially in the northern part, is characterized by flat areas or gentle slopes, suitable for agriculture or livestock breeding. The site of Mursia is located in the northwest of the island (Figure 3B), and is enclosed by a high cliff overlooking the sea and a massive perimeter wall of volcanic stones.

Pantelleria boasts a highly diverse flora (approximately 570 vascular taxa), shaped by its volcanic substrate, rugged topography, and marked ecological gradients. The island's vegetation ranges from coastal scrub to well-developed woodlands, reflecting both altitudinal variations and historical land use. At lower altitudes, the landscape is dominated by thermophilic shrublands, where P. lentiscus, O. europaea var. sylvestris , and E. dendroides prevail. These communities gradually give way to more structured formations, particularly in less disturbed areas. The woodland vegetation reaches its best expression in the higher, more humid central zones, especially around Montagna Grande. Here, extensive stands of Aleppo pine (P. halepensis) and maritime pine (Pinus pinaster) are present. More significant, however, are the remains of natural forests of holm oak (Quercus ilex), often mixed with Arbutus unedo, Erica arborea, and P. latifolia, which constitute the island's climax vegetation. On exposed ridges and drier slopes, the forest cover is fragmented, replaced by garrigue and gorse (Genista aspalathoides) and xerophytic plant species adapted to chronic water scarcity, such as T. capitatus, S. rosmarinus , and Thymelaea spp.

Pantelleria is home to a remarkable diversity of reptiles, birds, and invertebrates. Reptile species include the wall lizard (P. sicula) and the European gecko (Euleptes europaea), while small mammals such as the house mouse (Mus musculus) are widespread. The island lies along important migratory routes, attracting birds of prey and numerous passerine species during their seasonal movements. Coastal and marine habitats are particularly rich, with colonies of seabirds including herring gulls (Larus michahellis) and common shags (P. aristotelis). The surrounding waters are home to diverse fish populations, and occasionally dolphins and sea turtles, testifying to the ecological importance of the island's marine ecosystems (https://www.parconazionalepantelleria.it/).

3. Archaeological framework

The low altitude (and consequently limited visibility), the almost total absence of freshwater sources, the lack of precious geological resources such as obsidian, and the considerable distance from the north-western coast of Sicily make Ustica relatively marginal in the exchange dynamics of the southern Tyrrhenian Sea during prehistory. However, permanent human occupation began at least from the end of the Middle Neolithic (first half of the 5th millennium BC), as evidenced by recent excavations at Piano dei Cardoni (Speciale et al., 2020, 2021a, b, 2022, 2024b). These findings suggest the arrival of Neolithic groups in some areas of the island, coinciding with a general demographic increase in Sicily (Mannino, 1998; Speciale, 2024; Speciale et al., 2024a). These groups may have used the island as a springboard into the obsidian trade network and exchanges between the Aeolian Islands and western Sicily (Speciale et al., 2021b; Forgia et al., 2024). According to previous research, the island, once permanently occupied for the first time during the Middle Neolithic, was invested by a Neolithic subsistence economic system, with the exploitation of domestic and wild animals and plants and the processing of crops with local lithic tools (Mantia et al., 2021; Speciale et al., 2023). Despite the presence of imported obsidian and flint, all other resources were probably local. The island was in fact most likely independent in terms of basic food and livestock, with even a local production of ceramics (Speciale et al., 2021a, b, 2023; Magrı̀ et al., 2021; Prillo et al., 2024, 2025).

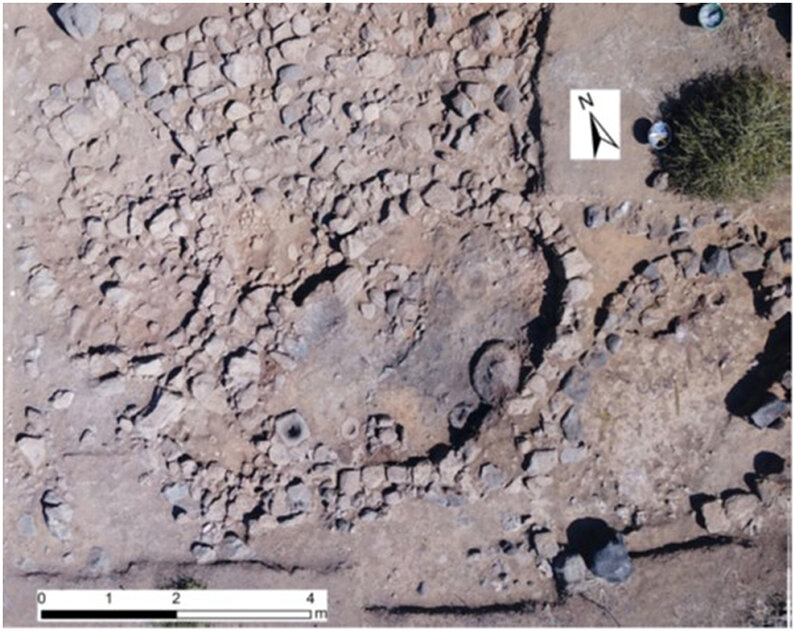

Following the distribution of ceramics and obsidian, the Neolithic site of Piano dei Cardoni occupied an area of approximately 2 hectares; AMS dating (Speciale et al., 2024b) confirms the chronology hypothesized through material culture (4800-4300 cal. BC). The megalithic funerary complex was located on the southern coast of the island ("Mezzogiorno"), not far from the modern-day city of Ustica. It was probably covered by an earthen mound; was excavated from 2019 to 2022 and revealed the funerary customs of this island community, recording a long process of manipulation of human bones and some rituals related to agricultural activities and the sun (Speciale et al., 2021a, 2023; Mantia et al., 2021; Magrı̀ et al., 2021; Montana et al., under review) (Figure 4). The sampled stratigraphic units presented here belong to the phases of use of the megalithic structure, in particular the filling of the pit, the group of bones around and on the stone slab, and the presumed earth mound above them. Being very close to the surface, data from potentially contaminated layers have not been included.

Figure 4. View of the funerary structure of Piano dei Cardoni (Ustica) before the removal of the big covering slab stone.

Figure 4

The prehistoric settlement of Mursia (Pantelleria) and its associated monumental necropolis, "I Sesi," are among the most significant and best-preserved archaeological complexes in the central Mediterranean. The settlement, which extends over approximately 1 hectare, is distinguished by its monumental defensive walls and large burial mounds, providing clear evidence of a complex society that deserves particular attention in archaeological research. The lifespan of this site is approximately three centuries and is composed of three macro-phases, spanning 300–350 years, from the mid-18th century to the mid-15th century BC (Cattani and Peinetti, 2023). The sediment samples analyzed from the Mursia site come from sectors B and E, each of which indicates distinct residential features dating to different phases of use of the village (Cattani, 2015; Debandi and Magrı̀, 2021). Sector B is identified as a residential area, with huts arranged in parallel rows, evidence of a deliberate and organized settlement layout. The sector is located on a rocky promontory at the northern edge of the lava flow, a location likely chosen for its strategic location and proximity to the coast.

The site was chosen for its favorable geographical characteristics: its dominant position on the Mursia plain, access to two potential landing points, and the presence of water coming from the coastal buvire. The topography of the promontory, partially spared by lava flows, was ideal for the settlement of the village. It is likely that the entire area, enclosed by the wall, was intended for settlement from the beginning. The samples from dwelling B14 correspond to the sixth occupation phase, which aligns with the first and second macrophases of the settlement (Debandi, 2015). These samples were collected from the stone structure of the hearth and its ash layers, while the samples from dwellings E1 and E2 fall within the third macrophase of the village, which is the last phase before abandonment. From this area, samples were collected from the ceramic and clay of the hearth with andirons, but also from the external space between two huts (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Mursia (Pantelleria, TP), Area E: zenithal photograph with huts E1 (right), E2 (center) (Debandi et al., 2019).

Figure 5

The village of Mursia demonstrates how Pantelleria was at the centre of exchange networks for precious materials and objects that linked the island to the eastern Mediterranean, the northern coast of Africa, and even northern Europe (Cattani et al., 2024). So far, no clear indicators of imported basic supply sources have been found, despite analyses having highlighted the presence of imported ceramics, and the isotopic signature of some faunal remains could indicate a potential provenance from outside the island (Dawson et al., 2024; Fiori et al., 2024).

4. Materials and methods

4.1 Cardoni Plan, Ustica

Some results have already been published in Mantia et al. (2021), Speciale et al. (2021a, 2023), Prillo et al. (2024, 2025). The first 14C datings, published in Speciale et al. (2024b), are obtained on faunal and macrobotanical remains. Soils were flotated during the excavation of Area 2 (years 2019–2020) of the Piano dei Cardoni site, when samples were systematically collected according to the standard procedure (Pearsall, 2015) of approximately 20 litres per layer. Some of the samples were contaminated by modern seeds or charcoal and were therefore not considered in this paper. In 2022, the sampling amount was increased and the team used a manual pump flotation machine, allowing a total of over 1,250 litres of sediment to be processed. Unfortunately, the density of macroremains is generally very low, probably due to the nature of the site (being a funerary structure, the presence of botanical materials is very limited) (Supplementary Material, Table 1). Furthermore, most of the plant material was poorly preserved and/or limited in size in the case of charcoal: specimens mostly range from 0.5 to 2 mm in width and are not always clearly visible on the three cuts. The remains were manually selected with a magnifying glass (4×) and then examined with an Optika B-383MET trinocular metallographic microscope (up to 500×). The carpological remains were observed with a Euromex binocular microscope (up to 50×).

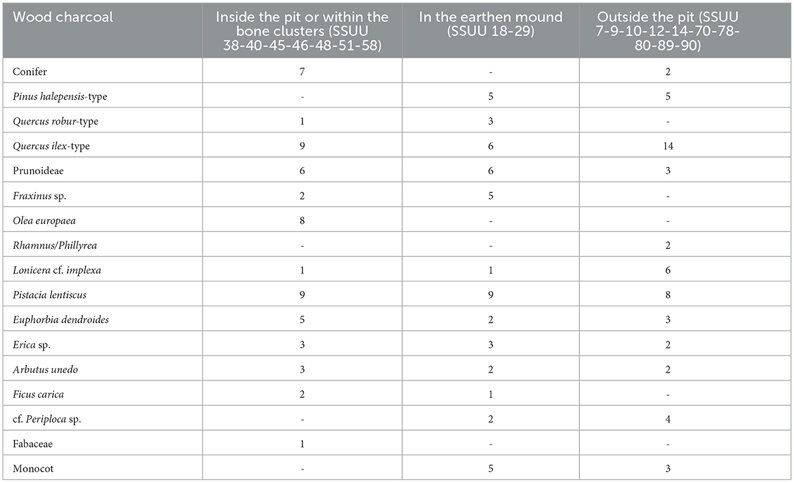

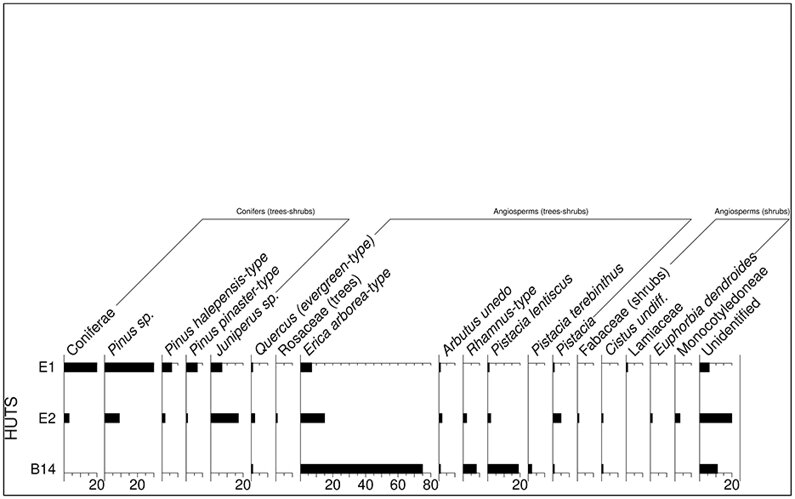

Table 1. Anthracological remains from Piano dei Cardoni (Ustica).

Table 1

For the identification of woody species, reference atlases (Cambini, 1967; Schweingruber, 1990), scientific literature (e.g., Asouti et al., 2015), and online tools were used: InsideWood, https://insidewood.lib.ncsu.edu and Microscopic Wood Anatomy, http://www.woodanatomy.ch/. For the identification of fruits and seeds, reference atlases were used (Neef et al., 2012; Sabato and Peña-Chocarro, 2021). Furthermore, the analysis was supported by direct comparison with the reference collection at the Archaeobotany Unit, IPHES-CERCA, when necessary. Due to their very low density in the soils, all charcoal and seeds were observed. The nomenclature of all plant species cited in the text follows Pignatti et al. (2017–2019).

Faunal remains were quantified by determining the number of identified specimens (NISP) for each taxon , while the minimum number of individuals (MNI) was calculated only for the most common ones following Bökönyi (1970) for most species and Girod (2015) for molluscs. Different osteological atlases were used for taxonomic identification: Schmid (2022) for mammals, Cohen and Serjeanston (1996) for avifauna, Giannuzzi-Savelli et al. (1999) for marine molluscs, while fish bone identification was conducted using online resources (Archaeological Fish Resource, University of Nottingham, n.d.; Tercerie et al., 2022).

To identify some bone remains, it was necessary to use a reference collection, therefore some materials were transferred to the Laboratory of ArchaeoZoology of the University of Salento (LAZUS, Lecce, Italy). The scientific nomenclature of domestic animals refers to Gentry et al. (2004). The distinction between sheep and goats was attempted using the criteria described in Boessneck et al. (1964), Boessneck (1969), Payne (1985), Halstead et al. (2002) and Zeder and Lapham (2010).

Data on epiphyseal fusion of long bones were recorded using the work of Silver (1969) for cattle, Bullock and Rackham (1982) for sheep and goats, and Bull and Payne (1982) for pigs. Tooth wear stages were recorded following the work of Grant (1982) for cattle, Grant (1982) and Bull and Payne (1982) for pigs, and Payne (1973) for sheep and goats.

The size and morphology of sheep and goats have been studied using standard log-weight index (LSI) values (Meadow, 1999). LSI values for postcranial bones were calculated using established caprine standards (Davis, 1996), also examining changes in sex ratio (Davis, 2000).

4.2 Mursia, Pantelleria

The 14C dates of Mursia were obtained on some hut contexts dating to the same phases as the huts presented here (Cattani, 2015), while new 14C analyses are underway to directly date the samples in this article. The bioarchaeological data from Mursia come from several excavation contexts and present partial sampling, as the island's very arid climate forces the preservation of freshwater as much as possible. Therefore, flotation of soil samples was limited for a long time, until archaeologists implemented an alternative protocol using seawater during the last excavation seasons. This manual flotation was carried out with two sieves with 2 and 0.5 mm mesh sizes, and only the floating residue was filtered with the smaller one. This type of flotation was followed by a final rinse with freshwater within the same day, exclusively for the small residue. This last action is essential to avoid the crystallization of sea salt and the potential degradation of the remains.

Each soil sample weighed approximately 5 liters, and the bioarchaeological remains were compared based on their volume. This method made it possible to overcome the problem of representativeness between the different categories, as well as the high fragmentation of the bioarchaeological remains (Supplementary Material, Figure 1).

Furthermore, this analysis involved a double sieving action by a zooarchaeologist and an archaeobotanist in two separate phases, and the volume of the remains was measured using three types of graduated containers of 0.5 ml, 2 ml and 16 ml.

The conservation conditions of the archaeobotanical remains from Mursia are rather good, with low levels of vitrification and crackling for the charcoal, despite their very limited dimensions.

Differences in the distribution and typology of bioarchaeological remains help clarify the use of spaces within the various housing units, for example: the analysis of floor layers, the waste disposal area, and the area containing kitchen ceramics.

The soil samples discussed in this paper come from sectors B and E of the Mursia site, each of which reflects distinct habitation characteristics associated with different phases of village life (Cattani, 2015; Debandi and Magrı̀, 2021). The samples from hut B14 belong to the sixth habitation phase, which corresponds to the first and second macrophases of the settlement (Debandi, 2015). The first two samples (B1001; B1002) were taken from the upper and lower fills of lithic cist SU 1097, a structure that supported the hut's hearth. The remaining samples from B14 (B1003; B1004) come from an ash disposal area (SU 1119), also associated with the area of this hearth. The samples from huts E1 and E2 correspond to the third macrophase of the village and refer to the final phases of the site's occupation. The first two samples from Structure E1 (E1501; E1504) were recovered from SU 2011 and interpreted as the occupation layer for activities within the hut. Along the eastern wall of this structure, a concentration of ceramic objects related to food preparation was identified, including two andirons and a cooking bowl. The other samples were collected from the fillings of a bowl-plate (E1507, Rep. E15036), from the interior of a small olla (E1509, Rep. E15024), and from the sediment surrounding the andiron (Rep. E15016; Debandi and Magrı̀, 2021). The samples from structure E2 refer to the surface of a beaten floor (SU 2067) and the ground surrounding the andiron (Rep.E16028; Debandi and Magrı̀, 2021), as well as a sample of the external space between huts E2 and E3 (SU 1201).

The classification of carpological remains was conducted using a binocular stereoscopic microscope (10x). Carpological remains were identified by comparison with atlases (Cappers and Neef, 2016; Neef et al., 2012) and with the reference collection of the ArcheoLaBio Bioarchaeological Research Centre (Department of History, Cultures, Civilizations, University of Bologna). Identifications were carried out using Leika and Konus stereomicroscopes (2x–7x magnification). For scientific nomenclature, Pignatti et al. (2017–2019), the Plants of the World Online (https://powo.science.kew.org/) and The World Checklist of Vascular Plants (https://www.gbif.org/) databases were used. All carpological remains found in the samples were examined.

Protocols for analysis of charcoal and faunal remains followed those described in Section 4.1.

4.3 Compared framework

The prehistoric human ecosystems of Ustica and Pantelleria are compared. The two islands exhibit notable differences in size, distance from the coast, and ecological characteristics. Furthermore, the two archaeological sites differ in chronology and function. Therefore, they offer a valuable opportunity for comparison to assess potential adaptations to the island environment. The combined analysis of carpological, anthracological, and faunal remains provides a comprehensive picture of how ancient communities interacted with their environment and their dietary choices. Carpological data contribute to understanding which plants were cultivated or harvested, while charcoal remains reflect the use of forests and local vegetation. Faunal evidence, in turn, provides insights into subsistence practices and animal management.

This multidisciplinary approach is mainly due to the fact that animal and vegetation management are inextricably linked and that, as mentioned above, in general the impact of animal grazing is particularly dangerous on limited geographical areas such as small islands (Anderson, 2002). Small Mediterranean islands likely required specific and deliberate adaptation strategies on the part of the prehistoric human groups who settled them (Ramis, 2014).

Over time, as human group sizes increased, anthropogenic pressure increased, and environmental conditions changed, these adaptive choices may have become more specialized, reflecting both ecological constraints and the need to manage limited resources sustainably. Signs of human adaptation include shifts in species composition toward more resilient taxa, evidence of landscape management (e.g., agroforestry, terraced landscapes; Bevan and Conolly, 2011), changes in herd composition (Ramis, 2017), and indicators of long-term resource sustainability (e.g., absence of taxa related to overgrazing) (Caballero et al., 2009).

5. Results

5.1 Cardoni Plan, Ustica

5.1.1 Anthracological data

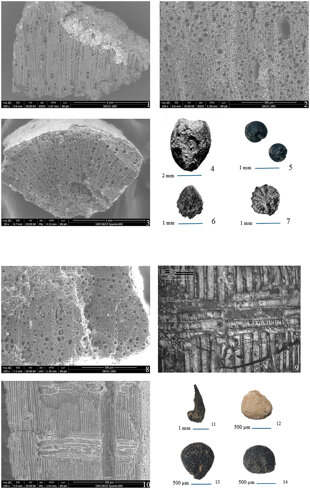

The first analysis of the anthracological data from Piano dei Cardoni is published in Speciale et al. (2023). The new data include the stratigraphic units excavated in 2020 and 2022 (Table 1, Supplementary Table S1). The initial results, very limited in terms of number of specimens, have been enriched with new species not previously detected. The newly analysed charcoal fragments, mostly of very small size, are presented here. This is the main reason why 25% of the record remained unidentified, despite a very low rate of vitrification and cracking. The taxa are fairly evenly distributed across all contexts, with the notable exception of olive trees, which are present exclusively within the burial pit and identified here for the first time (Figure 6.1). Most of the record is represented by local shrubs such as mastic (P. lentiscus), heather (Erica sp.) — Figure 6.2 — and spurge (E. dendroides), associated with an oak-pine forest (Aleppo pine and holm oak), which includes ash trees (Fraxinus sp.) and wild plums (Prunoideae), confirming the mesophytic association as previously reconstructed (Speciale et al., 2023). Also noteworthy is the probable first recovery of periploca (cf. Periploca sp.) and deciduous oaks (type Quercus robur), currently absent from the flora of Ustica, and of the fig (Ficus carica), perhaps imported from the mainland (Figure 6.3).

Figure 6

Figure 6. Anthracological and carpological remains from Piano dei Cardoni (1–7) and Mursia (8–14).

(6.1) Transversal section of Olea europaea charcoal;

(6.2) Transversal section of Erica arborea-type charcoal;

(6.3) Transversal section of Ficus carica charcoal;

(6.4) Hordeum vulgare subsp. vulgare caryopsis;

(6.5) Chenopodiastrum murale seed;

(6.6) Heliotropium europaeaum fruitlet;

(6.7) Althea hirsuta/Malva setigera fruitlet;

(6.8) Transversal section of Erica arborea-type charcoal;

(6.9) Radial section of Pinus cf. halepensis-type;

(6.10) Radial section of Pinus cf. pinaster-type;

(6.11) Triticum sp. glume;

(6.12) Ficus carica achene;

(6.13) Portulaca oleracea seed;

(6.14) Chenopodium sp. fruit.

5.1.2 Carpological data

The carpological heritage of Piano dei Cardoni is rather limited, due to the nature of the site. 353 specimens have been identified, in addition to the 13 previously recovered (Speciale et al., 2023) (Table 2, Supplementary Table S1). 14% of the charred fragments were not identified (including lumps and carpological tissues with a volume greater than 1 mm3). The preservation conditions are generally not very good, especially for the remains recovered from the earth mound. The only identified cereals are hulled barley (Hordeum vulgare subsp. vulgare, Figure 6.4); other Poaceae were found, some of which were identified at genus level (Poa, Lolium) and widespread in all contexts. Legumes are limited at the family level and absent from the earthen mound, while Chenopodiastrum murale (cf. Chenopodiastrum murale, Figure 6.5) is certainly the most represented taxon in all contexts in terms of number of specimens, followed by heliotrope (Heliotropium europaeum, Figure 6.6). Some plants have a very low representation, such as hairy mallow (Althaea hirsuta, Figure 6.7), black nightshade (Solanum nigrum) and black bindweed (Fallopia convolvulus). Parts of mastic fruits and probable acorns were recovered in almost all contexts. In general, the lowest diversity is found within the pit, where species are mostly limited to Poaceae, Fabaceae, C. murale and H. europaeum.

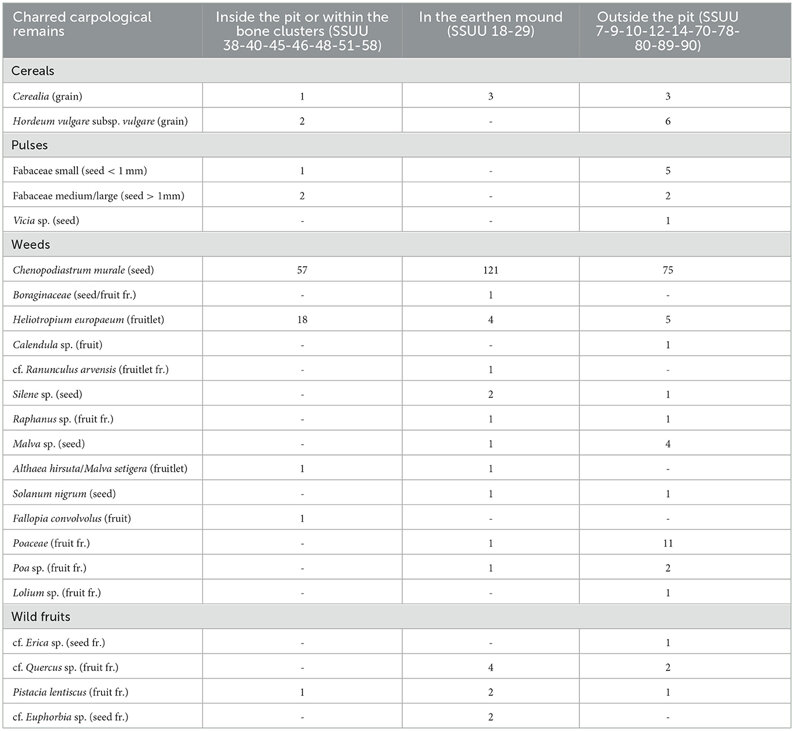

Table 2. Carpological remains from Piano dei Cardoni (Ustica).

Table 2

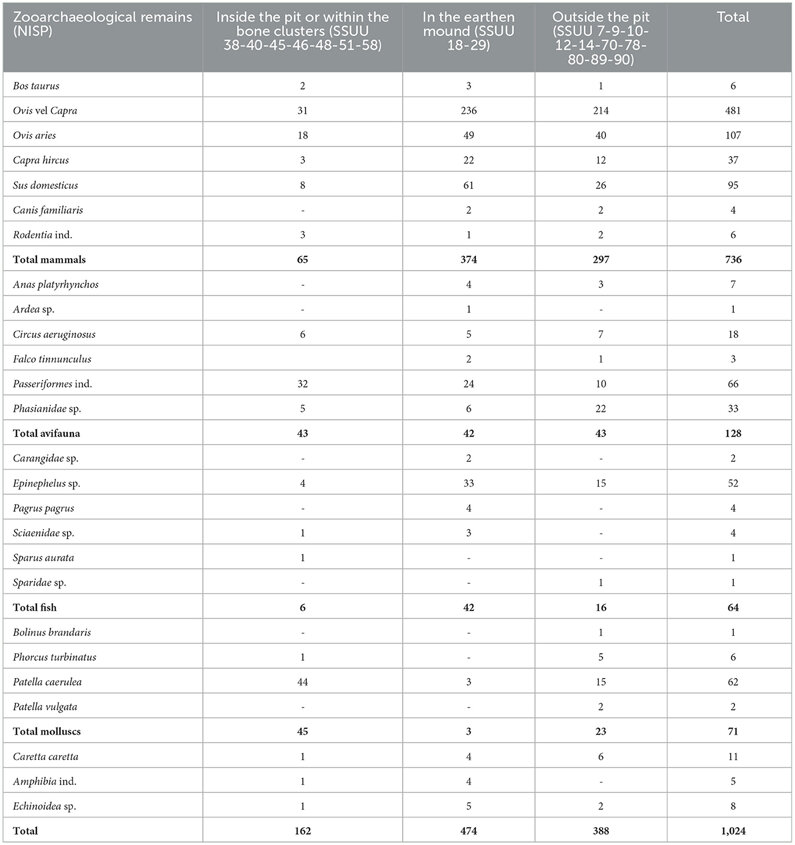

5.1.3 Zooarchaeological data

The data presented here are an updated version of those published in previous studies (Prillo et al., 2024, 2025), now also including the materials found during the 2022 excavation campaign. Furthermore, the zooarchaeological data are presented considering each specific context (Tables 3, 4), as done with the carpological and anthracological data, thus excluding faunal remains from unreliable or less significant stratigraphic units.

Table 3. Zooarchaeological remains from Piano dei Cardoni (Ustica) quantified by their NISP.

Table 3

Table 4. Minimum number of individuals (MNI) of the most frequent animal species identified from Piano dei Cardoni (Ustica).

Table 4

The faunal sample is composed primarily of mammalian bones, with a clear dominance of sheep and goats. Sheep (Ovis aries) consistently outnumber goats (Capra hircus), although bones classified in the general category of sheep and goats (Ovis vel Capra) are the most abundant. Pig (Sus domesticus) remains are also present in modest quantities, while cattle (Bos taurus) remains are almost absent. Mortality profiles for domestic species indicate a predominance of mature individuals, suggesting a focus on maximizing meat yield by allowing the animals to reach their optimal size. However, the presence of some piglets and young sheep and goats indicates that younger animals were also occasionally consumed.

No wild mammal species were identified in the archaeological contexts considered in this study, although the presence of rare remains of hare (Lepus sp.) and fox (Vulpes vulpes) was recovered in most surface layers (Prillo et al., 2024, 2025). Hunting focused exclusively on avian species, which were intensively exploited. However, the most frequently hunted birds were small and medium-sized species, particularly the marsh harrier (Circus aeruginosus), the common kestrel (Falco tinnunculus), and members of the Phasianidae family and the Passeriformes order. Together with the presence of mallard (Anas platyrhynchos) and red-billed storks (Ardea sp.), these species suggest the presence of bodies of water on the island during the Neolithic.

Marine resources also played a significant role in the diet of Ustica's Neolithic inhabitants, as confirmed by the presence of numerous fish remains, mostly groupers (Epinephelus sp.), and mollusc shells, particularly Patellidae. Due to their fragmented state, biometric data for fish species are not available; however, the presence of groupers and other fish families (Carangidae, Scianidae, Sparidae) suggests the exploitation of medium-to large-sized prey. Finally, other exploited marine species included sea turtles (Caretta caretta) and sea urchins (Echinoidea sp.).

Finally, preliminary biometric data suggest that sheep and goats were smaller in size than those from other contemporary contexts in Sicily and southern Italy. This aspect will be explored in detail to determine whether insular factors contributed to this size variation.

5.2 Mursia, Pantelleria

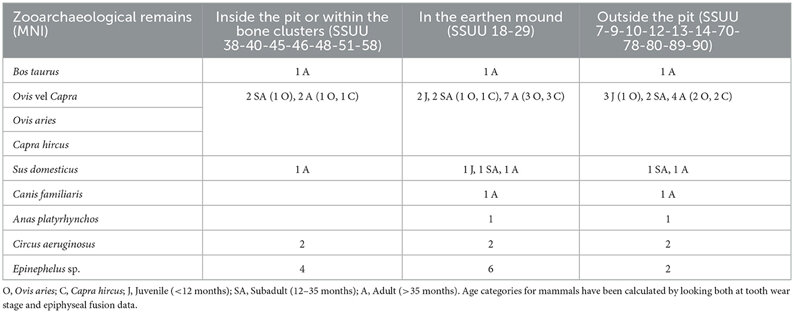

5.2.1 Anthracological data

A total of 300 charcoal samples were recovered and analyzed (Figure 7, Supplementary Table S2). Approximately 10% of the charcoal fragments were unidentified, mainly due to their small size. The preservation rate is quite good, with minimal evidence of distortion or fungal attack. In the B14 hut assemblage, tree heather (type E. arborea) dominates (almost 70%, Figure 6.8). Other shrub species are present in smaller proportions, including strawberry tree (A. unedo), privet (Rhamnus/Phillyrea), rockrose (Cistus sp.), mastic tree, and terebinth (Pistacia cf. terebinthus). Fragments of the Q. ilex type are very scarce.

Figure 7. Percentage and table with the number of specimens of wood charcoal from huts B14, E1 and E2.

Figure 7

Wood gathering and usage appear to shift in the next phase, represented by huts E1 and E2. Conifers become the main tree species exploited (75% in E1, 50% in E2). Pines (Pinus sp., type P. halepensis and maritime pine, type Pinus pinaster, Figures 6.9, 6.10) dominate E1 (50% of the total), and Juniperus sp. is slightly more represented in E2 (almost 30% of the total). In E1, the remaining 25% comprises shrub species, along with a small percentage (2%) of type Q. ilex. In E2, over 3% of type Q. ilex, cf. E. dendroides, Cistus sp., Rhamnus/Phillyrea, Fabaceae, and monocots are also present.

5.2.2 Carpological data

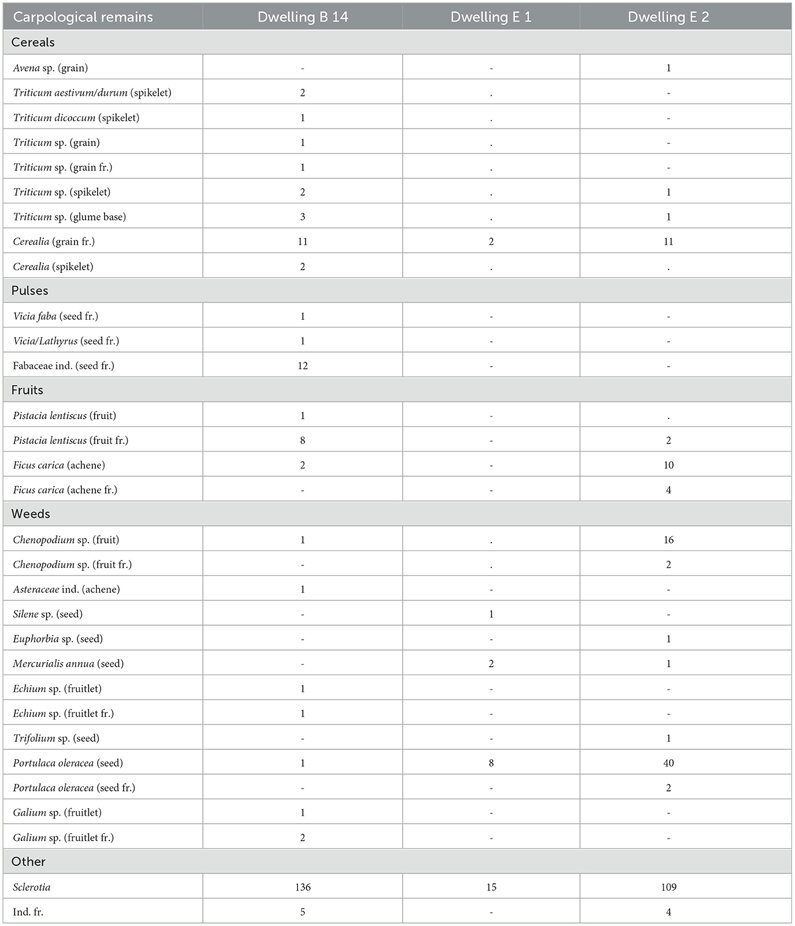

Carpological analysis shows a high number of charred seeds and fruits in dwellings B14, E1 and E2, while very few mineralized remains are present (Table 5, Supplementary Table S2).

Table 5. Carpological remains from Mursia.

Table 5

Soil samples revealed the presence of domesticated plants, including common wheat (Triticum aestivum/durum), emmer (Triticum dicoccum) (Figure 6.11), broad beans (Vicia faba), and other legumes (Vicia/Lathyrus). In particular, concentrations of emmer were found specifically within the stone hearth structure of dwelling B14, while a single oat grain (Avena sp.) was recovered from the outdoor space between dwellings E1 and E2. Wild plants were also identified in these same samples: fig (Figure 6.12) and mastic were present. F. carica was more common in samples from the third macrophase, while P. lentiscus was abundant in the first/second macrophase of the site. Furthermore, various herbaceous species found in the samples could be used for many purposes. For example, purslane (Portulaca oleracea) (Figure 6.13), an edible plant, and goosefoot (Chenopodium sp.) (Figure 6.14), potentially edible depending on the species, were found mainly in samples from dwelling E2. Annual mercury (Mercurialis annua) and some species of rennet (Galium sp.) can be used to dye fabrics (Guarrera, 2006; Prigioniero et al., 2020); the former was attested in the third macrophase and the latter only in the first/second macrophase. Other Mediterranean plants, such as viper's wort (Echium sp.), spurge, catchfly (Silene sp.), and clover (Trifolium sp.), were identified at the site, which were possibly used by the villagers for pharmaceutical purposes (e.g., Sheydaei et al., 2025; Kolodziejczyk-Czepas, 2016).

A high number of sclerotia (clusters of fungal hyphae) were found in the same soil samples, which depend on the organic properties of the layers. As expected, their number is irregular across the samples, but a high concentration was found within the stone structure of the hearth of dwelling B14.

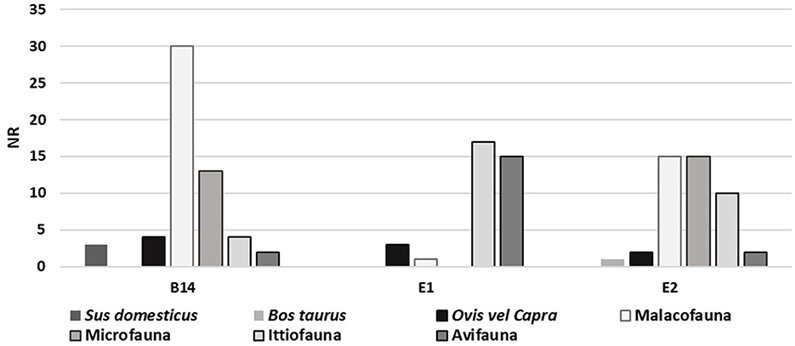

5.2.3 Zooarchaeological data

The zooarchaeological analysis of the Mursia site focuses primarily on the first and second macrophases of the village, based on the faunal remains recovered from settlement B14 (Figure 8). In contrast, data from the third macrophase are limited and derive exclusively from the analysis of soil samples associated with settlements E1 and E2, as presented here. The samples from B14, the second macrophase, include 38,051 osteological remains. Of these, approximately 23% have been taxonomically identified and anatomically described.

The data show a subsistence economy centered on livestock farming, with a predominance of goats (C. hircus) and sheep (O. aries), followed by pigs (S. domesticus) and cattle (B. taurus). On this island, hunting of large wild mammals was not practiced because wild herbivores were absent. However, the exploitation of marine resources and the capture of wild birds played a significant role. As expected, fishing was particularly important and focused on medium-sized and large species caught near the reef, including dusky groupers (Epinephelus marginatus), wrasses (Labrus sp.), gilt-head breams (Pagrus pagrus), and parrotfish (Sparisoma cretense). In addition, the villagers collected various families of molluscs (Patellidae, Trochidae, Muricidae), sea urchins (Echinoidea), crabs (Eriphia sp.), as well as cuttlefish (Sepia sp.), sea turtles (Caretta caretta), and even monk seals (Monachus monachus). Migratory birds also provided a valuable seasonal source of meat during migration, as evidenced by the remains of greylag goose (Anser sp.) and Yelkouan shearwater (Puffinus yelkouan).

Figure 8. Faunal remains from Mursia. NR = NMI.

Figure 8

In contrast, preliminary zooarchaeological data from the third macrophase indicate an increase in cattle and a decrease in pigs within the livestock population. This trend seems to be supported by previous studies (Wilkens, 1987), although further data are needed to confirm this hypothesis (Fiori, 2025).

6. Discussion

6.1 Ustica

6.1.1. Woody resources and fruit trees

The site is dominated by shrubs such as mastic, heather, and spurge, associated with a mixed forest of oak and pine, with the presence of ash and wild plum trees. Furthermore, periplochium, deciduous oak, and fig trees were also identified for the first time on the island. One of the most notable findings is the presence of olive trees exclusively within the pit, where they were recorded for the first time at the site. The high biodiversity observed in such a small record suggests the absence of selective breeding, with harvesting likely involving species from different areas of the island.

This broad-spectrum exploitation may reflect several factors: 1. the island's small size, making it easily traversable in a day; 2. its naturally low biodiversity, influenced by its limited surface area and low altitude; and 3. the low number of diverse habitats due to environmental homogeneity. Furthermore, 4. the apparent lack of preference for any particular tree species may have led to a more balanced exploitation of resources, distributing human impact evenly between shrubland and forested areas, thus reducing the risk of overexploitation.

Both evergreen and deciduous oaks were present on the island, with the latter identified here for the first time. Deciduous oaks are absent from the island's current flora. Their presence on a small and relatively flat island like Ustica is a clear indicator of rather humid conditions, consistent with broader Mediterranean climate trends during the mid-fifth millennium BC (Speciale et al., 2024a). Such conditions likely also contributed to creating a favorable context for human settlement on the island. The new data also confirm the presence of holm oaks, ash trees, and Aleppo pines in the island's natural vegetation, consistent with previous findings (Speciale et al., 2023). On the other hand, the potential presence of periploca (probably Periploca angustifolia, also present in the Egadi Islands, Pantelleria, the Pelagie Islands, and the Maltese archipelago) is recorded for the first time in the Tyrrhenian insular context. This deciduous summer taxon is adapted to extremely arid conditions; it is a shrubby species with various uses in phytopharmaceuticals (Huang et al., 2019).

The fig is recorded here for the first time. In mainland Sicily, F. carica increases in most lake pollen sequences from the mid-6th millennium BC (e.g., Calò et al., 2012). Its spread probably parallels that of domesticated cereals, although its only presence in an archaeobotanical record as a fruit so far dates to the mid-6th millennium BC in the Uzzo Cave (Speciale, 2024). It remains uncertain whether the fig was naturally present on the island before the arrival of humans; however, its introduction by humans during the Neolithic appears more plausible. Wood analysis cannot help unravel the exploitation of its fruits, and, so far, no fig achene has been found in the carpological record; its exploitation therefore remains an open question for Neolithic Ustica. The picture is the opposite of Mursia, where fig achenes are present but fig charcoal is absent.

The olive tree is present both in the Sicilian lake pollen record and in the Mesolithic layers of Grotta dell'Uzzo, where it was identified as olivastro (Speciale, 2024), and exploited as far as the Madonie mountains at least since the Bronze Age (Forgia and Oll?, 2023). Its presence in the Neolithic phase of Ustica was uncertain from previous records and is now confirmed. The cultivated olive tree (O. europaea L. var. europaea) is believed to have originated from the domestication of its wild form (O. europaea var. sylvestris (Mill.) Lehr), which grows spontaneously throughout the Mediterranean basin. The distribution of the olive tree mostly aligns with that of its wild ancestor, one of the most representative taxa of Mediterranean sclerophyllous vegetation (Carrión et al., 2010; Gianguzzi and Bazan, 2020).

Undoubtedly, from the Bronze Age onwards, the marked increase in olive tree remains is closely linked to olive oil production (Caracuta, 2020; Palli et al., 2025; Schicchi et al., 2021). This process is also evident in the Middle Bronze Age finds from Ustica (Speciale et al., 2023) and could indicate localized domestication dynamics, particularly in southern Italy (D'Auria et al., 2017). Olive exploitation on small Mediterranean islands is frequent after the 4th millennium BC. On another small island, Cephalonia, from the Chalcolithic to the Middle Bronze Age, the increasing presence of Arbutus sp., indicative of increasingly open landscapes, is correlated with the increasing presence of O. europaea, also prominent in the Heraion plot of Samos (Ntinou and Stratouli, 2012; Mavromati, 2022).

In other geographic areas, the introduction of tree crops on islands suggests the gradual evolution of forest management towards agroforestry (Dotte-Sarout, 2017). Arboriculture has become a significant component of production systems in the Marquesas Islands (Huebert and Allen, 2016, 2020), the Society Islands (Lepofsky, 1994), and Tikopia (Kirch and Yen, 1982). Agroforestry usually represents the last step in the process of landscape management development, commonly starting with the clearing of coastal vegetation (Huebert and Allen, 2016). On a small Mediterranean island like Ustica, however, it appears that occupation occurred all at the same time and that the exploitation of wood resources was somehow managed from the beginning.

Finally, O. europaea charcoal at Piano dei Cardoni was recovered only from within the burial pit. The presence of olive trees in funerary contexts elsewhere in southern Italy is particularly significant. The oldest evidence of olive pits, dating to the Middle Neolithic, was recovered from a funerary context at Carpignano Salentino (Lecce) (Ingravallo and Tiberi, 2008). The use of olive wood persisted until the Copper Age, when it continued to have ritual value, as evidenced by its use in funerary practices at the stone mound of Macchia Don Cesare (Salve, Lecce) (April and Fiorentino, 2018).

6.1.2. Crops and weeds

The carpological remains recovered at Piano dei Cardoni are relatively few, likely due to the unfavorable preservation conditions. Nevertheless, the increased volume of flotation soil samples significantly increased the quantity of remains recovered in the latest campaign.

Barley is the predominant cereal, while other Poaceae, such as Poa and Lolium, are present and evenly distributed across the different contexts. Their presence could indicate human use or their role as fodder. Many of the identified weeds may have grown in arable fields, entering the site through tillage or other agricultural activities. Some potentially edible plants are present, such as goosefoot leaves (C. murale), which may also have been sown in fields for animal grazing (Behré, 2008). Whether some of these plants were deliberately collected for medicinal or food purposes, for example, is difficult to determine from the generally small quantities recovered, as well as the poor preservation that limits their identification.

Legume diversity at Piano dei Cardoni is low, with no remains recovered from the earthmound. Small-seeded legumes may have grown in arable fields, including stubble, or in pastures. After C. murale, H. europaeum is the most common taxon. Although its presence may be associated with agricultural activities, the relatively high numbers suggest it may have had a specific use: it is traditionally used as a medicinal plant for its analgesic properties. A few fragments of acorns and mastic nuts were found in most contexts, indicating the exploitation of local wild resources. The pit context presents the lowest taxonomic diversity, dominated by Poaceae, Fabaceae, C. murale, and H. europaeum.

Among cereals, barley stands out for its drought resistance, as its grains mature before the driest Mediterranean phase in May. This characteristic likely explains its general preference, particularly in island environments (Pérez-Jordà et al., 2018; Stika et al., 2024). For example, during the loss of crop diversity in the Canary Islands, barley was the cereal that most clearly "resisted" until the arrival of the Spanish, likely due to its lower requirement for genetic enrichment and greater adaptability in isolation (Morales et al., 2023; Hagenblad and Morales, 2020).

The exclusive presence of barley at Piano dei Cardoni is consistent with patterns observed at early Neolithic sites in Calabria. Wheat becomes more common from the Middle Neolithic onwards, with an overall increase in crop diversity during this period. In Puglia, for example, Triticum spp. is dominant (Costantini and Stancanelli, 1994; Natali and Tiné, 2002), although species distribution varies significantly between regions (Natali et al., 2021). In Sicily, however, archaeobotanical data for this phase remain limited (Speciale et al., 2024a). It is therefore impossible, at this stage of research, to determine whether the predominance of barley at Piano dei Cardoni indicates a cultural choice or an adaptation to local environmental characteristics, although it is worth noting that barley was preferred among other cereals on the small volcanic islands of Sicily until recently (Speciale, 2021).

6.1.3 Animal breeding, hunting and fishing

The site's fauna is dominated by mammalian remains, with a clear predominance of sheep and goats (O. aries being more abundant than C. hircus). Pig (S. domesticus) remains are present in moderate quantities, while cattle (B. taurus) are almost absent, as expected on an island with limited water resources. Mortality profiles suggest that animals were raised to maturity to maximize meat yield, although young individuals, particularly piglets and young sheep and goats, were also consumed.

The introduction of wild animal species to Mediterranean islands is not uncommon and is also observed in other insular contexts (Masseti, 2006; Hofman and Rick, 2018). "Niche enhancement" can occur when human groups take measures to increase the population and availability of their prey, for example by introducing them to islands to establish huntable populations. One of the earliest recorded examples is the introduction of the cuscus, a marsupial, from New Guinea to New Ireland approximately 23,500 years ago. On Ustica, the introduction of the hare and fox remains uncertain (Prillo et al., 2024).

Hunting activities were primarily aimed at birds. The most frequently identified species include the mallard (A. platyrhynchos) and the heron (Ardea sp.), suggesting the existence of small water reserves on the island during the Neolithic, likely corresponding to modern whirlpools (Speciale et al., 2023). However, the most frequently hunted birds belong to predatory taxa, similar to pheasants and sparrows. In particular, the presence of birds of prey, such as marsh harriers, in secondary burials, alongside more commonly consumed species, suggests intentional consumption rather than accidental presence. If these birds were intrusive, more complete skeletons and a wider range of anatomical elements would be recorded. Instead, the concentration of wing bones (e.g., ulna and carpometacarpus) indicates selective inclusion, likely linked to ritual practices (Prillo et al., 2024). Furthermore, the consumption of birds of prey in island contexts is not unexpected. Subsistence strategies on islands often relied on the full range of available animal resources. The exploitation of wildlife, particularly birds and small mammals, is typically more intense on islands than on the mainland and, in some cases, has contributed to local extinctions (Rick et al., 2013; Bover et al., 2016; Médail and Pasta, 2024). The association of wetland-related bird taxa suggests the persistence of freshwater areas during the Neolithic.

Marine resources played an important role in the inhabitants' diet, as indicated by the numerous fish and mollusc remains. The potential presence of medium-sized and large fish could indicate the use of relatively advanced fishing techniques, a hypothesis further supported by the presence of bone hooks and stone weights (Mantia et al., 2021).

It is increasingly recognized that the introduction of (over)grazing livestock and other animals, such as rats, has often had dramatic effects on island ecosystems. These changes may have significantly altered the original landscape, making the islands appear more marginal or impoverished than before historical times (Fitzpatrick et al., 2015). Sheep and goats from Ustica were smaller in size than those from other contemporary sites in Sicily and southern Italy. Although further investigation is needed, this reduction in size may reflect human management strategies shaped by the island's limited resources. A similar trend of reduction in body size under environmental pressure is recorded, for example, in the Bronze Age in the Balearic Islands (Valenzuela, 2023; Valenzuela-Suau et al., 2023) and in the modern era in cattle from Pantelleria (La Mantia, 2018). As noted by Schüle (1993), large mammals on small islands are usually naturally absent, due to their potential to rapidly deplete local vegetation.

6.2. Pantelleria

6.2.1. Woody resources and fruit trees

The use of wood on Pantelleria during the Bronze Age is characterized by the exploitation of forest and shrub species, primarily pine (both Aleppo and maritime), evergreen oak, mastic, and heather. This is the first time that archaeobotanical analysis has described the co-occurrence of two different pine species on the island, dating back to at least the second millennium BC—likely reflecting their natural presence before the arrival of humans, a presence that has continued to the present day. Heather and other Ericaceae, such as strawberry trees, are known to grow several meters tall, especially on the islands, and it is therefore highly likely that the exploited individuals were arboreal rather than shrubby. A small quantity of juniper was also recorded, particularly in the pine-rich layers, suggesting their shared presence within the same vegetation formation. The absence of deciduous oaks, which are recorded in the pollen sequence of Lake Venere many centuries later (Calò et al., 2013), is significant. It is unclear why the Bronze Age inhabitants of Mursia excluded deciduous oaks from any type of timber supply. The presence of oaks has so far been limited to holm oak, recorded in the three huts, while heather and mastic are prevalent in the hut in sector B and pine and juniper in sector E.

The absence of olive trees stands out as unusual compared to the general trend in Sicily, especially considering their documented presence in the Pantelleria record during the Punic and Roman periods (Speciale et al., unpublished data) and in the Lago di Venere sequence (Calò et al., 2013). At the current state of research, it is unclear whether olive trees were absent from the natural vegetation and only introduced by humans at a later stage, or whether their absence in these hut layers—an absence also recorded in the carpological record—is simply a matter of chance. What is certain is that olive trees were quite widespread in the central Mediterranean in the Middle Bronze Age (see Section 6.1.1).

Compared to the rather diverse timber exploitation of Ustica, evidence from Pantelleria suggests a more selective exploitation of trees, likely highlighting changes over time. However, the data set is too limited to determine whether the variation in species representation between the first/second and third village macrophases reflects a real shift in economic strategies and timber use. Certainly, a general trend towards greater aridity is documented around 1550 BC (Speciale et al., 2016, 2024a). Despite this climatic drought, the archaeological record indicates a marked increase in population, a relationship inversely proportional to climatic conditions. This apparent resilience may be attributed to improved methods for managing drought and food stress, as well as the development of extensive trade networks and logistical infrastructures typical of more complex societies (Palmisano et al., 2021).

Comparing data from the Aeolian Islands during the Bronze Age, Ericaceae emerge as the dominant plant family, used both for construction and as fuel, particularly on the island of Filicudi, and are also widely represented on Lipari. On the latter island, the greater diversity of charcoal remains demonstrates the island's heterogeneous shrub and tree vegetation, which includes pines, deciduous oaks, holm oaks, poplars, Fabaceae, and olive trees (Special, 2021).

In the Balearic Islands, at the Passes Seis site, a dynamic exploitation of forest resources is evident, demonstrated by the inversely proportional trends in the use of pine and mastic trees (Picornell-Gelabert and Carrión Marco, 2017). A similar inverse relationship is observed between the huts in sectors B and the huts in Mursia.

In particular, arboriculture is often an important source of subsistence on the islands (as demonstrated for figs and olives in Neolithic Ustica, but more generally, see for example Huebert, 2014). In Mursia, wild species were an important source of subsistence probably during the third macrophase, but the presence of fig achenes, even though F. carica is absent from the charcoal record, indicates a potential importation of tree species, as seen on Ustica, from the mainland, or the exploitation of imported syconia, especially during the third macrophase.

6.2.2. Crops and weeds

As observed in the shift in wood harvesting practices, the use of economic plants also appears to change along the occupational sequence. In the first and second macrophases, domesticated plant species predominate. Hulled wheat and bare grain are likely the exclusive cereals, and legumes also play an important role. The significant presence of mastic fruits during these phases corresponds to their high representation in charcoal, suggesting a broader use of this plant resource. In contrast, the third macrophase is characterized by a greater presence of weeds, particularly purslane and goosefoot. Despite this shift, cereals remain part of the assemblage, although they appear in more degraded condition, which may reflect taphonomic factors influencing their preservation. The presence of these remains within the huts strongly suggests human consumption. However, it is unclear whether the wild herbaceous taxa in the Mursia carpological assemblage represent exploitation of native plants, inadvertent introductions as weeds alongside cultivated plants, or deliberate introductions for their nutritional and/or medicinal properties.

In the Aeolian Islands, during the Bronze Age, crop exploitation patterns show considerable variability. At Filo Braccio (Filicudi), there is a strong representation of hulled barley and legumes, particularly lentils and broad beans. In contrast, the data from Lipari refer only to the final phase of the Bronze Age and reveal a more heterogeneous use of cultivated plants (Special, 2021).

Shifting cultivation appears to have been among the earliest agricultural strategies adopted on many islands (e.g., McCoy, 2006). Typically, island agricultural systems begin with the introduction of a limited number of plants, followed over time by increasing specialization, a dynamic described in several contexts (Fitzpatrick and Keegan, 2007; Fitzpatrick, 2015). In Polynesia, Kirch (1984) has delineated this trajectory as one of adaptation, expansion, and intensification. Defining clear stages of development in the Mediterranean is difficult. This complexity arises from frequent cycles of occupation and abandonment, the close connections between many islands and the mainland, and the strategic importance of islands such as Pantelleria in broader exchange networks (Dawson, 2014). However, the significant exploitation of wild plant species during the Bronze Age can be interpreted as an adaptation strategy to local resources and/or a response to broader climate changes, such as those that occurred in the mid-16th century BC (Speciale et al., 2024a, see also Section 6.2.1).

6.2.3 Animal breeding, hunting and fishing

Terrestrial animal resources at Mursia are not highly represented in the hut contexts presented here, while marine resources (fish and molluscs) appear to be more prominent, along with birds of various sizes, similar to the pattern observed at Ustica. Sheep and goats dominate throughout all macrophases, while pigs and bovids are recorded in lower numbers. The absence of dogs is significant; this seems to contrast with the increase in bovids and the decrease in pigs in the last phase, despite livestock being herded onto land by herding dogs. However, the absence of wild predators and the limited extension of the territory likely allowed local strategies that made livestock husbandry possible without the use of dogs. Data are still too preliminary, but a shift in husbandry strategy during the village occupation cannot be ruled out (Fiori, 2025), also considering the general increase in aridity during this phase, contrasting with the greater water requirements of cattle compared to other livestock. Finally, recent isotopic analyses on faunal remains belonging to the first and second macrophases have opened the possibility of importation of animals from the mainland (Dawson et al., 2024).

Marine resources played a significant role in the diet at all stages, as did avifauna. This suggests that wild marine fauna and birds, readily available on the island, continued to constitute an important part of the subsistence economy even during the Middle Bronze Age, a pattern that contrasts somewhat with the broader trend in southern Italy and Sicily, where a decline in the exploitation of wild resources is generally observed (De Grossi Mazzorin et al., 2004; Arena et al., 2020; Speciale et al., 2024a). The presence of harbor seals, found among marine animals, was very common in Sicily until recently (La Mantia and Pasta, 2008). The substantial reliance on meat-based resources in Mursia is consistent with dietary trends observed in the Italian peninsula (Varalli et al., 2022), although only stable isotope analysis of human remains can clarify to what extent plant-based foods contributed to the Bronze Age diet in Mursia.

In the Aeolian Islands, the fauna from the small island of Filicudi during the Early and Middle Bronze Age is dominated by sheep and goats, although both pigs and cattle are present. The low representation of marine resources can be attributed to excavation methods, while terrestrial wild animals are absent. At the multi-layered site of the Acropolis of Lipari, a clear diachronic trend is observable: from the Neolithic to the end of the Bronze Age, the representation of cattle and pigs increases, while sheep and goats remain consistently present. This trend is accentuated by the most significant socio-cultural transformation, which occurred between the Middle and Late Bronze Ages, when the arrival of people from southern Italy may have led to a marked change in dietary practices (Speciale, 2021; Villari, 1996).

Compared to other small Mediterranean islands, the pattern diverges slightly. During the Neolithic, smaller islands in the Aegean and Adriatic appear to favor the exploitation of marine resources (Pilaar Birch, 2017), a trend also observed on larger islands under population pressure (Arikan, 2023). However, during the Bronze Age, feeding strategies in coastal areas appear to change (Nuttall, 2021). In the western Mediterranean, Formentera (Balearic archipelago) stands out from its larger neighboring islands, likely due to its geographical features, with a relatively higher proportion of wild animal remains in the faunal record (Ramis, 2017).

6.3. Adaptation to insular features in Ustica and Pantelleria

Strategic voyaging and the transplantation of plants and animals were critical to the success of colonization, facilitating both subsistence and cultural continuity (Anderson, 2009). The array of animals and crops provided not only protection against potential resource shortages, but also a symbolic marker of identity and a psychological anchor in unfamiliar environments (LeFebvre and Giovas, 2009), albeit adapted to the new island context.

Overall, the three Piano dei Cardoni datasets reveal how Neolithic communities adapted to the island environment through:

- A heavy dependence on a diversified economy that combined wild plants, cultivated crops, and domestic produce from land and sea resources.

- The heterogeneous exploitation of woody species from all potential series present on the island, probably due to the poor plant diversity in such a small and flat island environment and to a choice of low overall impact on the local vegetation.

- The preference for barley as a potential adaptation to rather arid local conditions or to some specific food choice, while the dependence on wild plants is quite common during the Middle Neolithic even in non-island environments.

- Domestic animal species, which reflect those of the mainland, although adapted to the constraints of the island, particularly in terms of water and forage availability, are highly dependent on sheep and goat farming of limited size and with very few pigs and cattle (Prillo et al., 2024, 2025).

- The entire economic system, based on limited agriculture, but also on significant exploitation of wild fauna resources: targeted hunting of birds, typical prey of the islands, and marine resources.

For the Bronze Age settlement of Mursia, indicators of island adaptation are less evident: Pantelleria is more than ten times larger than Ustica and features a significant altitudinal gradient. Furthermore, Bronze Age communities are based on a more structured and complex society. Compared to other islands—Ustica, Lipari, and Filicudi—Pantelleria exhibits parallels but also unique local responses, likely due to being the largest and most diverse in terms of habitat variety, but also the most isolated of the case studies. Nonetheless, potential indicators include:

- The wood composition, which reveals an integrated use of local forest and scrub species, including the co-presence of Aleppo and maritime pines, evergreen oaks, mastic, heather, and juniper. Previously, human groups relied more heavily on scrub species such as mastic and heather, later beginning to exploit holm oaks, pines, and juniper more intensively. This shift in fuel and wood management should be further studied, including the absence of deciduous oaks.

The absence of olive trees, in contrast to their known prevalence elsewhere in the central Mediterranean, raises questions about local environmental conditions or cultural preferences, particularly the production of mastic instead of olive oil. Changes between the first/second and third macrophases—evident in the use of wood, the consumption of cultivated and wild plants, and the management of animal resources—indicate a potential shift in exploitation strategies, perhaps in response to climate stress around 1550 BC and increasing social complexity.

- The extensive exploitation of wild plant species during the Middle Bronze Age, such as mastic and purslane, together with cereals and legumes and a cash crop such as the fig, highlights a flexible subsistence system and exploitation of drought-tolerant plants.

- Marine and avifaunal remains dominate the faunal record, indicating a strong reliance on readily accessible wild resources, in contrast to some mainland trends during the 2nd millennium BC.

- The potential importation of livestock from the mainland, which required a lot of water and was therefore probably unsuited to living on an island, especially in a phase of greater aridity such as that of the mid-16th century BC.

7 Conclusions

Similarly to other island contexts, even in the prehistoric Mediterranean, "individuals and collectives within societies are not exclusively environmental stewards nor agents of harmful ecological change" (Lepofsky and Kahn, 2011: p. 330), but act under a variety of socioeconomic and cultural motivations, as well as environmental constraints and opportunities, each constantly evolving. Nonetheless, resource management remains one of the most crucial aspects of human settlement on small islands.

This work demonstrates how multidisciplinarity represents the only meaningful approach for analyzing resources on islands and, more generally, in archaeological contexts (Table 6). The carpological, anthracological, and faunal analysis of the Piano dei Cardoni site provides significant insights into the plant and animal resources used by the inhabitants of Ustica during the Neolithic, that is, after the first permanent occupation of the island. The presence of plant species now absent from the island, such as deciduous oaks, heather, and strawberry trees, suggests climatic or environmental variations compared to the present day. The choices made by human settlers during their colonization process, likely bringing tree crops such as figs and olives, and not just herbaceous crops, tend to indicate a clear intent for long-term sedentary occupation of the island.

Table 6. Comparative table with the main plant and animal species from the two case studies.

Table 6

For the island of Pantelleria, no data on its Neolithic occupation are currently available. Therefore, data from the Bronze Age site of Mursia demonstrate human adaptation to a landscape that may have already been influenced by 3,000 years of previous human occupation. Nonetheless, Pantelleria is naturally more ecologically diverse and rich in resources than Ustica, and it is unclear whether Neolithic populations permanently occupied the island. Archaeobotanical and zooarchaeological data from Mursia offer the first multidisciplinary insight into Bronze Age resource exploitation on Pantelleria, highlighting both continuity and transformation in subsistence strategies. Ultimately, the Bronze Age human community of Mursia appears to have exploited diverse local ecological niches, while also being embedded in broader Mediterranean networks of exchange and innovation.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Authors contributions

CS: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MCar: Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. FF: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. VP: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EA: Data curation, Writing – review & editing. MCat: Funding acquisition, Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare having received financial support for the research and/or publication of this article. The postdoctoral fellowship with CS for the project "SILVA - Sicilian small IsLands Vegetation under the effect of human arrival" is part of the European Union's Horizon 2020 research and innovation program MSCA-COFUND R2STAIR (GA 101034349). IPHES-CERCA has received financial support through the "María de Maeztu" program for Units of Excellence (CEX2024-01485-M/funded by MICIU/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) and 2023: URV-PFR-1237; 2024: URV-PFR-1237, SGR 2021-1237.

Acknowledgments

Soprintendenza dei Beni Culturali di Palermo, Giuseppina Battaglia; Valeria Giuliana and Fondazione Mirella Vitale for the economic support of the investigations on Ustica; Istituto Nazionale di Geofisica e Vulcanologia, Osservatorio Vesuviano, Sandro de Vita and Mauro Di Vito. For the SEM pictures, we thank Mercè Moncusí from the Servei de Recursos Cientifico Tècnics at the Unversitat Rovira i Virgili (Tarragona). We sincerely thank the editors and the reviewers for helping us in improving significantly the manuscript. Salvatore Pasta gave us as well his notes and comments and we are thankful for his constant support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided with figures in this article was generated by Frontiers using artificial intelligence, and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure its accuracy, including review by the authors where possible. If you encounter any issues, please contact us.

Publisher's Note

All statements expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, nor those of the publisher, editors, or reviewers. Any products reviewed in this article, or any claims made by their manufacturers, are not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

Supplementary material for this article is available online at:

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fearc.2025.1621064/full#supplementary-material

References

Are inside the .pdf file to download.

Copyright

© 2025 Speciale, Carra, Fiori, Prillo, Allu´e and Cattani. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.